January 2022

placeGladstone, QLD

Gladstone: Possibilities for change through a collective impact approach

A case study of a Stronger Places, Stronger People Initiative - funded by the Department of Social Services

This case study was compiled during the second half of 2021, where members of the Stronger Places, Stronger People Gladstone initiative were interviewed by Collaboration for Impact (CFI) team members who have worked closely with the Start-up Backbone team, initial working group and leadership group. This case study shares the insights and experiences of Gladstone from the early phase, with a view to building a deeper understanding of how collective impact is being used to disrupt disadvantage and create better futures for children and their families in partnership with the local community.

“I think hope is the reason why we keep showing up. It's the hope that this could be the answer, this could be the way that we can change things and do things differently” Lorna McGinnis, Working Group Member

This case study follows the early journey of a collective impact initiative in Gladstone, Central Queensland, supported by the Stronger Places, Stronger People initiative of the Australian Government in partnership with the Queensland government.

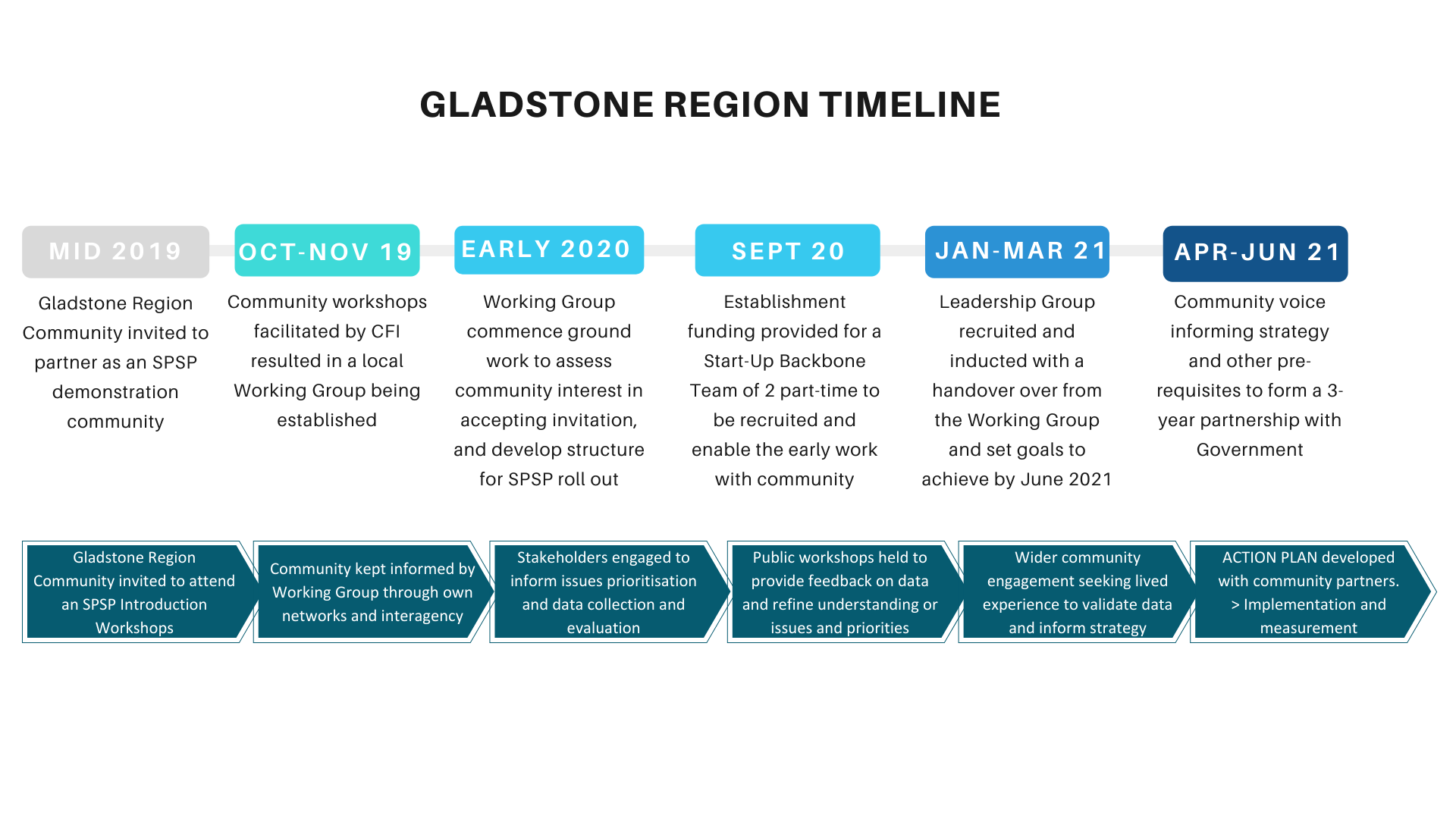

In mid-2019 the Commonwealth Minister for Families and Social Services and the Queensland State Minister for Communities invited the Gladstone Region Community to partner in the Stronger Places, Stronger People initiative, as one of 10 demonstration communities across Australia.

The Stronger Places, Stronger People (SPSP) initiative is a community-led, place-based initiative, that seeks to disrupt disadvantage and create better futures for children and their families, through evidence-driven solutions to local problems, in partnership with local people. SPSP is built on a Collective Impact model and a shared commitment to a local strategy by communities, governments, service providers and investors, with shared accountability for planning, decision making and outcomes.

At the time the invitation to partner was presented, Gladstone had experienced concerning growth across a number of indicators associated with worsening disadvantage in community. At this time there was not a whole of community collective impact initiative in Gladstone.

Gladstone has a reputation for being a comfortable, high-income, industry town, but just below the surface of the attractive regional city lifestyle, a significant proportion of the community were struggling and demands on services indicated that the number of people finding life challenging was rising.

The way that I understood it in the early stages was that government were partnering with community to influence wellbeing in the future. Being a parent here in the Gladstone region, that just really spoke to me, not just for my family but for those families and children that maybe haven't had as much opportunity as we have had here. That was the thing that really interested me” Lorna McGinnis, Working Group Member

To support the partnership offer from the Australian and Queensland Government, governments funded foundational support. Foundational support began with workshops held in Gladstone by support partners Collaboration for Impact (CFI) and PwC Indigenous Consulting (PIC). The workshops were designed to support community in their understanding of Collective Impact practice and were part of a Partnership Exploration Process to support the Gladstone community to decide if the SPSP partnership was right for Gladstone. As a result of the workshops, a local Gladstone SPSP Working Group was established to consider the partnership offer in-depth and what it would mean for the Gladstone Region.

Conversations with stakeholders identified that:

- Gladstone had displayed great strengths over the years in coming together to address specific identified topics of need, including in response to domestic and family violence or to improve access to mental health supports, but these efforts occurred mostly in siloed pockets

- Examples of collective identification of community values and aspirations existed, however these had occurred as short Industry funded projects to guide local community investments and while resulting documents were gifted to community for use, they were now gathering dust on shelves

- Momentum to progress beyond aspirations, to active problem solving or measurement of outcomes, ceased each time the funded resourcing stopped

- It was acknowledged that the most disadvantaged community members were less likely to engage in formal consultation, and so the voice of those experiencing life’s challenges the most may often be missing from the conversation

Community members shared that while local momentum for change was being felt by stakeholders, collective efforts to improve community wellbeing were less mature than desired.

The SPSP partnership with Government presented the opportunity to build a collective and holistic approach to improving wellbeing across the Gladstone Region, with paid resources to consistently drive the work locally and maintain the momentum.

Collaboration for Impact (CFI) and PwC Indigenous Consulting (PIC) supported the newly formed Working Group to harness existing levels of readiness and build the initial steps towards a local leadership group for a change initiative, driven by a shared purpose.

The Gladstone SPSP Working Group of 15 members formed with the intent to:

- consider and seek community interest in accepting the partnership offer from Government

- decide on the geographical area SPSP would cover within the Gladstone Region

- recruit a locally employed Start-Up Backbone Team

- review and collate previous community consultations to identify recorded aspirations

- recruit and orientate a local Leadership Group to take the work forward

Working Group members were excited by the commitment of Governments to resource the work and enable a community-led, place-based approach to creating change. Members were interested in collective impact practice and people from Gladstone had engaged in learning about collective impact in the years prior. However, it took time and conversations to establish if the SPSP partnership offer was right for Gladstone. Members were inspired and encouraged by the demonstration of Government to be equal partners at the table and open to seeing Government and Community as part of the solution.

A determination of the group was to acknowledge the good work that had already occurred in Gladstone. Having seen many community-consultation visioning and change projects come and go and ‘start from scratch’ each time, there was a strong desire to build upon existing community consultation works and to leverage the knowledge and experience that existed in the community. The foundational support funded by governments and delivered by PIC and CFI enabled the working group to start differently, with community owning how implementation began and building on what existed in Gladstone.

“It just seemed such a great opportunity to utilise the opportunities that I've been given over the last 15 years in Gladstone and leverage the community knowledge and the networks that I’ve built here.” Lorna McGinnis, Working Group Member

The desire to adopt continuous progression allowed the early work of the Gladstone SPSP initiative to be fast-tracked by leveraging what was already known about the region, the challenges it experienced and the strengths it offered. The use of publicly available population data and a desktop review of the numerous social and economic impact reports on the region allowed the Start-Up Backbone Team and early Working Group to capture the history and status of the region in a short period. This allowed time for extensive engagement with a wide cross-section of stakeholders to seek validation that the capture was reflective of lived experience and still current.

A causal factor for the rising disadvantage observed, was identified as a reoccurring trend in fluctuating unemployment, welfare dependency and social services demands, related to economic ‘boom and bust cycles’ and its relationship to migration in and out of the region.

- Gladstone is an industrial town and relies on coal export, alumina, aluminium, cement and LNG

- Population growth and migration cycles are influenced by industry construction projects with knock on effects for rental prices that disproportionately impact the disadvantaged

- Unemployment rates fall during construction projects that recruit large temporary workforces and rise higher than the regional averages during bust periods that follow construction completions

- The fall in rental prices that occur following a Boom, relate to large workforce numbers leaving town for employment opportunities elsewhere, this in turn makes Gladstone an attractive relocation option for renters from outside the region experiencing financial hardship

- Domestic and Family Violence, Mental Health, Drug use and Children in Care were noted as significant issues for the community which also showed correlation to migration patterns

This raised a significant challenge for the work. By identifying that an important factor impacting wellbeing statistics for the region was migration, it effectively meant that the goalposts would keep shifting.

To measure change in wellbeing accurately, migration would need to be constantly quantified as an uncontrolled variable. This was an important outcome resulting from the early collaboration of services to share their experiences.

While capturing migration as a variable in the measurement of wellbeing was an identified challenge, recognising its role in the work provided the opportunity to name it and quantify it so that it could be addressed. A more intangible challenge was the mindset shift for local stakeholders from Government directed and funded programs to community-led action.

Habitual tendencies to work within funding eligibility guidelines, within the confines of contractual deliverables, under the direction of government, made it challenging for community members to accept that they were being given the authority to direct the work from here forward.

“People quite understandably are action-oriented. There's an urgency. We want community change, and we want to know how to do that. We want to know how much money we've got to do it, and we want to know what the government wants us to do. In these early phases it is very easy to slip back into old ways.” Bec Crompton, CFI, Working Group Facilitator

Some members found it hard to trust that this new way of working with government allowed community to create their own direction and tended to default to a desire to seek government approval or direction at each step of the journey.

It was surprising to many community members that they might be the most equipped to identify and assess the needs of community and that there was no other entity accountable for monitoring and measuring wellbeing in the region to ensure that life in the region was progressing in a positive direction.

“We were naive, we really didn't realise that there wasn't a department, organisation or business unit that was sitting down, bringing all the data together for our community, and evaluating where we're at, and what we needed to do to improve things in the future. We just assumed that somebody was out there doing that, but we weren't part of that conversation.” Lorna McGinnis, Working Group Member

Members in the SPSP Working Group had to understand a whole new approach and explore relationships and power in a new way, trusting in their capacity to find the answers from within community instead of looking to those outside for direction.

“In those early, first 12 to 18 months there was so much ambiguity, and there was so many different things to consider for the new working group and there was that real feeling and sense that they didn't have authority to make decisions on behalf of community.” Deb King, Start-Up Backbone Support

The biggest challenge for the Working Group though was the feeling of ambiguity about the group’s role and what the work ‘looked like’. The initial stages of the SPSP model required community coming together in a learning space, to first understand the model underpinning the initiative. This was uncomfortable for those wanting to get started on the work. References were made to experiences of ‘talk-fests’ with no outcome. This was particularly felt by members feeling the weight of responsibility, conscious that making the most of this opportunity for the community rested with them in those early stages of what was a finite funding period.

An additional pressure for Working Group members was timing. The balance of understanding the work enough to effectively articulate the opportunity to others, while feeling compelled to share the opportunity as early as possible, resulted in a dilemma. The question of ‘when’ was too early or too late to engage more broadly was a major hurdle that continually resurfaced as Working Group Members wrestled the internal battle of not wanting to exclude anyone, with the risk of disengaging stakeholders if the initial contact appeared too vague or disorganised.

As information did start to trickle out to the community in the desire to engage early, there was some scepticism among service providers, resulting from seeing other well-intentioned initiatives fail in the past. The question “how will this be different?” was a trend in the early stages, as stakeholders grappled with trusting this new shift to power being placed in the hands of community to be a part of the solution.

What began to make a difference was the conviction with which the Working Group members were able to convey to others that Government genuinely wanted to understand what the limitations and challenges were within the existing service system and to work together differently to achieve improved outcomes. This level of equity and trust suggested a vulnerability within government that humanised them as a stakeholder and built confidence in others that all stakeholders could work together for solutions with equal skin in the game.

“It takes bravery and courage to be able to come and be vulnerable as a collaborator, together, sharing information, sharing learning, sharing ways that we can all work better together, rather than in silos like we're used to doing.” Deb King, Start-Up Backbone Support

Taking an authentic approach to community-led action meant that the way of working together was quite different. The ‘usual’ suspects, prominent in other community initiatives, made way for new faces at the table, which required a level of patience and generosity to allow space for newer voices to the conversation to become familiar with the current social landscape. And for those that were more embedded in the social sector, there was a period of adaption to adjust to the slower, community-led pace.

“I’ve been to a number of things, and it's just Powerpoint slides and going through the motions. This was much more intimate, thoughtful and engaging with more sensitivity for what’s trying to be achieved. A real genuine feeling that they want to see change for our region as well.” Leanne Patrick, Leadership Group Member

This new way of working together played out in who showed up for the work from community and how individuals participated and interacted. From the early days of the initial Working Group established in late 2019, to the induction of a Leadership Group in early 2021, the mix of stakeholders driving the initiative was rich and diverse.

“Working collaboratively is bringing like-minded people together, but from very different and varied backgrounds. And when we all come together, we each bring a skillset and knowledge that is quite unique to our situations. But when you put that all together, I believe it forms a great foundation for build change in the community.” Leanne Patrick, Leadership Group Member

The new approach impacted on individuals personally as well as shifting group dynamics, significantly changing the way some members thought about themselves and how they reacted to others.

“What's beautiful to see is when people show up to meetings and you can see these penny-drop moments of, ‘Oh, that feels different. That looks different. That sounds different... I don't really understand it, but I want to be a part of it’ and trusting that instinct.” Bec Crompton, CFI, Working Group Facilitator

Some members reported taking some of the ‘ah-ha’ moments, related to deep listening or power and equity awareness into other parts of their life, in their approach to family members or with work colleagues and noted that they felt a different response in themselves and a changed outcome with others.

Power Equity

Another element of the new approach was that unlike government led consultation, the level playing field created when community is the one asking questions, provides opportunity for a new frankness that overcomes perceived risks related to telling the ugly truth of things. It became evident that the community-led model increased the depth of engagement and provided more licence for providers to share the realities of service delivery without fear of imagined consequences.

“Traditionally, the biggest problem of government and service providers working together is that there’s a power imbalance. This unintentionally sets the tone for the entire relationship. The power imbalance inhibits authentic conversation and equal partnership to solve issues and can lead to inherent hostility and lack of trust towards government.” Lorna McGinnis, Start-Up Backbone Lead

Conversations with human service sector stakeholders, whose existence is predominately dependent on government funding, revealed a fear of sharing information about challenges, capacity limitations or inhibitors to outcomes, with government partners. The fear that visibility of service delivery shortcomings might result in the organisation missing out on further funding, or the region missing out on needed supports, created a self-imposed disempowerment. This limited the level of trust that could be built between partners in the funding relationship. Without trust, the shared accountability required to productively find solutions together was restricted.

Insights into the extent of the perceived power imbalance in funding relationships and its impact on program success was evident in service provider feedback in relation to reporting practices and program measurement.

“In Gladstone we've known for a while that we're only reaching those that are easy to reach. Service providers are meeting their contract obligations, they've got the outputs and are ticking the boxes, but they are also aware that there are community members that are most in need of their support that they just haven't been able to engage with.” Lorna McGinnis, Start-Up Backbone Lead

The community-led aspect of the work reduces the power imbalance and cuts through some of the arm’s length courtesy protocols that often inhibit real conversation, so that issues can be dissected, and effective solutions can be developed.

Local Content

In the Gladstone experience, a chief element in making the work authenticity community-led and place-based was the employment of a local Start-Up Backbone Team to support the early work. During the early stages of the project, many local conversations were required with community and stakeholders to direct the development of the work. Having a locally employed team with lived experience of some of the idiosyncrasies, challenges and opportunities of living in the region, was pivotal in building local relationships.

While engagement with wider ‘grass roots’ community had been an inclusion of prior initiatives, the depth of engagement had often been limited by finite allocations of resources and time. Consultation was often attached to a ‘stage’ of a project, such as initial fact finding, or draft design consultation, where community are invited in as guests to participate for a defined period and in a defined way. The SPSP model enabled the shift from an engagement ‘window’ to an ongong conversation and allowed community to partner in the work, at the table, alongside other stakeholders.

“The benefit of community having a really strong voice in the work is they've got lived experience and understanding of what has worked for them, what has supported them to be able to improve and overcome challenges. If we can understand that, and duplicate it, then more people are then going to be able to reap the benefits.” Deb King, Start-Up Backbone Support

Constant ongoing communication is a core pillar of the Collective Impact framework and the SPSP model. The SPSP model is unique in resourcing the Backbone team in a way that authentically enables this, (not funding a service provider). As a result, the depth of conversation required to really identify the challenges and blockers to wellbeing can be reached, and lived experiences can shape the planning, instead of others without lived experience making assumptions to fill the gaps.

“Working in this way, community-led and in partnership with government, is different to the usual top-down approach. It’s different because it requires community members to really get to know each other in a much deeper way and across all sectors of community, whether it's services, mums on the street, grandparents, or whoever it is that's showing up in the work.” Bec Crompton, CFI, Working Group Facilitator

Community Values and Commitment

Community commitment to the work was significant from its earliest days. The Gladstone SPSP Working Group invested over 1,200 community hours in establishing the initiative between November 2019 and March 2021 and paved the way for the newly established Leadership Group to submit a partnership proposal to Government in June 2021.

As the SPSP initiative started to evolve in Gladstone and input from wider voices was threaded into the work through stakeholder consultations and community engagement outcomes, articulation of the work and the values that underpinned it locally, started to surface with more confidence and clarity.

Values established early in the work, included an appreciation that authentic conversation does not come from a one-size-fits-all consultation model, and that lived experience and the voice of First Nations people in the region was fundamental to the work. Initial contact with stakeholders focused on seeking their preferences of engagement style, this included workshops with stakeholders for feedback on preferred geographic locations, venues, formats and language use to enable access to engagement opportunities.

This approach enabled deeper conversations with community, including with Traditional Owner Elders, which was considered to be a respectful and essential first step in engaging with the wider First Nations community.

Being authentically community-led meant also allowing the pace and format of engagement to be directed by the preferences of individual stakeholders and stakeholder groups. This was a tricky balance in some cases, including engagement with First Nations community members, where non-First Nations community members felt compelled to advocate for and ensure that first nations voices, were in the work from the start. Trusting that stakeholders would decide for themselves how and at what pace they wanted to engage, meant also trusting that the order in which things happen can be flexible and project timelines should not take priority over the choice of individuals to engage when they were ready.

“This work has allowed us to have some different conversations with our First Nations Elders in Gladstone, we have had some long in-depth conversations about why this is different to things that we've done in the past. But our elders tell me, "It's a long, slow process." Lorna McGinnis, Start-Up Backbone Lead

Another key value was to ensure that the work be actions and outcomes driven. In reflection of this and in recognition of the many stakeholders that would need to be involved for the initiative to be successful, in mid 2021, as Gladstone SPSP morphed into its new structure in partnership with Government and auspiced by CQUniversity, the new community-led change movement was named ‘Gladstone Region engaging in action Together’.

Flexible and patient

“The work of Stronger Places, Stronger People is ground-breaking. It is asking communities and governments to demonstrate working in a very, very different way.” Katie Holms, Department of Communities, Disability Services and Seniors.

This new way of working, modelled by the SPSP initiative, offered to be a game changer in the power balance between government and community. Participating at the table together for the same goal and with an open rule book, opened the door to have more challenging conversations about the root cause of issues without fear of tripping over authority boundaries or upsetting the funding cart.

“The real partnership, the real sitting together and trying to work together on a solution often gets missed. And it's always been a frustration of mine, because I've worked with government, and I've worked with those that are receiving funds from government. And so I can see both sides of the coin. And I can see that nobody is to blame, but there's still a gap.” Lorna McGinnis, Start-Up Backbone Lead

An element of success in the development of the initiative is identified as the ‘space’ Government partners have given community to understand and build trust in the process and build the foundations themselves.

“I actually think the fact that the government were involved from day one but took a back seat until we needed to hear from them was a good thing. I think had they been there at the table constantly, it might have hindered things a bit more.” Kate Duffy, Working Group Member

Community have noted that rather than adopting a ‘cookie-cutter’ approach, governments have been flexible and adaptive using a tread lightly approach which has been received positively as it meant that the community members felt they have had a free hand (to lead), while still feeling supported through the foundational support and engagements with governments when they requested them.

“They have been very mindful not to come in and influence. So they've given the Working Group and the Leadership Group that space to be able to determine what it is and to set their path, rather than coming in with a whole lot of rules and timeframes and expectations.” Deb King, Start-Up Backbone Support

The ability to talk to government in an honest way, as a genuine partner without the inherent power imbalance being felt in the room, has been vital to the success of the Gladstone initiative's establishment.

“Having government partners at the table, and really being able to share where we're at in a very transparent way without feeling like it might inhibit our future opportunities with that partner, made a difference to what we can talk about and the context we can provide.” Lorna McGinnis, Start-Up Backbone Lead

Making the invisible visible

Data played a significant role in understanding how the Gladstone Region community is experiencing disadvantage and to pinpoint where disadvantage is occurring.

The relationship with government partners was significant in providing the trust required across other government departments to share sensitive data that was not available through any other means.

Statistics revealed that there was potentially a higher number of children in the Gladstone Region living in disadvantage or at risk, than anyone had been aware. Shared data provided insights into numbers and locations of families finding life challenging which can now inform program design and target locations for program delivery.

“So how we used data was exceptional, I think. We've really drilled down to the nitty gritty and what we actually found was data was in conflict. On one side something looked not so bad, but actually when you drilled down a little deeper with the data, there was actually a massive problem.” Leanne Patrick, Leadership Group Member

Data sharing by governments with the community-led initiative helped to make the disadvantage that is “invisible” and unknown, transparent to everyone in Gladstone. The raw data revealed a side of Gladstone that many were unaware of.

“It's not what we experienced day-to-day when you walk around our community and there's no visibility of homelessness, there's no visibility of alcohol and other drugs on our streets. So we as a community, were really quite blinded to this hidden element of disadvantage that the data has started to reveal.” Lorna McGinnis, Start-Up Backbone Lead

A major contributor in overcoming previous limitations in understanding fluctuations in community wellbeing was the sharing of government data related to migration of families receiving welfare as a statistical variable. The movement of families from other local government areas or states was central to understanding the role of migration on welfare statistics. Being able to quantify whether a rise in families finding it tough in the region results from existing locals needing to seek welfare support, or as a result of existing welfare recipients moving into the region, is significant in developing an appropriate response to most effectively support our families.

“The opportunity that we have now is to delve deep into, where is disadvantage occurring? Who is experiencing it? Why are they experiencing it? What is it that we are doing as a community that isn't helping that situation?” Lorna McGinnis, Start-Up Backbone Lead

Using the data to effect change

The data became a useful tool to engage in conversations with leaders in the community and governments. Crucially it provided the evidence base to direct and develop change strategies.

“When we started having conversations about our intentions to pull the data together so that we could really understand where the need was, there was just this relief that you could see on people’s faces, because they would have the evidence to demonstrate that what they knew in their hearts to be true, because they were talking to families and understanding what was happening on the ground.” Lorna McGinnis, Start-Up Backbone Lead

Data, and accurate interpretation of the data, is an important part to telling the ‘right story’ of the Gladstone community. GRT intends to weave statistical data together with lived experience as shared through conversations with community. Telling the personal story of the human impact behind the numbers, through video and written case studies will help bring the statistics to life.

The Gladstone Region Wellbeing Data Hub will bring together wellbeing indicators across different sectors and make data more available to community in a way that it can be used by everyone to work together in making life better for everyone in the region.

The foundational support provided by SPSP has been critical in developing the leadership and governance conditions for collective impact and providing structures and processes to support the work being undertaken by the locally-led initiative.

While all SPSP demonstration communities are addressing their own unique issues and opportunities, the similarities across communities in goals and process challenges offered the Gladstone Community with a support network, facilitated by CFI and PIC in their role of connection and resourcing.

“It’s been very kind of messy, staggered, natural process, but it helped having that reassurance from government and the consultants that it's okay to not know the answers, and it's okay, that the script might change as you go and that the biggest achievement is bringing people along on that journey.” Deb King, Start-Up Backbone Support

The support from PIC and CFI was instrumental in the early processes of setting up the Working Group and the Leadership Group within the Collective Impact framework to embed the model and process. Foundational support provided by CFI helped recruit (with a working group member), employ and support the Start-Up Backbone team.

“The support has been endless and ongoing. From the word go, the support has been at any time that we've required it. There's a level of comfort that comes with knowing that you always have some type of support in the development of this work, because this work is so complex, it's very easy to get off task. And when you have the right support and organisations, they empower you to stay on track… I don't think we could have been where we are without that help, reaffirming the work constantly. Keeping us on the same vision.” Leanne Patrick, Leadership Group Member

Listen to Kate Duffy, Working Group member, speaking about what support looks like:

The success of Gladstone Region engaging in action Together (GRT) will be demonstrated in the measured outcomes it achieves for individual and community wellbeing.

The challenge that those in the work explain, is that the complexity of disadvantage seen and the many variables and interrelated issues impacting the lives of individuals, which requires response across multiple sectors. Prior to SPSP this challenge often landed in the ‘too hard basket’, with service providers stretched to crisis point in response to the immediate demand on their doorstep as needs escalated.

A common catchphrase in the early stages of the work was the ‘start-somewhere’ approach, biting off one piece at a time, to avoid being overwhelmed by the magnitude of the complexity.

“At first glance it looks like a very simple process, but it's so complex. So for me it was so overwhelming, but so exciting at the same time. Our long-term goal will be to disturb or disrupt disadvantage within our community. So I think you need to look big, but you need to start somewhere and you need to do it differently. You do the same thing, you get the same result.” Leanne Patrick, Leadership Group Member

One of the early successes for Gladstone was the wide engagement and collection of issues identified across multiple stakeholders and trusting the process enough to go with the flow and pace required to narrow down the focus area to be addressed within the fixed funding period. The end result was a Theory of Change which bought together in a one-page document, all of the areas identified as vital to creating change in Gladstone.

The GRT Theory of Change identifies the foundational conditions that are required to enable the journey and practical actions that will shift the dial towards improved wellbeing, including open transparent information sharing, trust, acting together, adaptability, and courage to challenge the status quo.

“It's the energy, it's very hard to articulate, but the success we are seeing, is the energy. For example, the energy we are seeing in our Traditional Owner Elders to want to share this work, and to want to have a voice at the table, and to really own that, so that it's not somebody else inviting our Traditional Owner families or First Nations people to the table, to have a voice.” Lorna McGinnis, Start-Up Backbone Lead

Early indicators that the community are on the right path are seen in the way that stakeholders are working together and the aligned themes that are emerging from feedback across all stakeholders groups about the approach that should be taken. These are the first steps towards a shared agenda and action plan and have been achieved through an unwavering commitment to building trust and relationships as a priority.

“Showing up into this type of work serves to really future-proof the community and give them a much stronger foundation from which to work either on what's happening with Stronger Places, Stronger People and the goals through that or being able to pivot to new challenges that might come along.” Bec Crompton, CFI, Working Group Facilitator

There is strong sentiment in the community that all the work that has been put into these early phases in Gladstone will reap great rewards for the community going forward.

“I think collaboration is here to stay. Collective impact is here to stay. It's a culture that people have to have embedded. SPSP for me and for a lot of people gave us access to that culture that can now be translated into other contexts.” Kate Duffy, Working Group Member

Find out more about

Other case studies

Change Cycle Locator Tool

Take the quick survey to work out where you are on your change journey and access information specific to your needs