January 2022

placeCeduna, SA

Far West SA: Possibilities for change through a collective impact approach

A case study of a Stronger Places, Stronger People Initiative - funded by the Department of Social Services

This case study was compiled during the second half of 2021, where members of the Stronger Places, Stronger People Far West SA initiative were interviewed by Collaboration for Impact (CFI) team members who have worked closely with the Backbone team. This case study shares the insights and experiences of Far West SA with a view to building a deeper understanding of how a collective impact approach is being used to disrupt disadvantage and create better futures for children and their families in partnership with the local community.

“It's important for it to be community-led because at the end of the day, community want to have a say in what is affecting our own lives. And if we can have influence in that, we're able to shape our own destiny and our own future. – Wayne Miller

The following case study is of a collective impact initiative in Far West, South Australia, supported by the Stronger Places, Stronger People and Empowered Communities initiatives of the Australian Government in partnership with the South Australian Government.

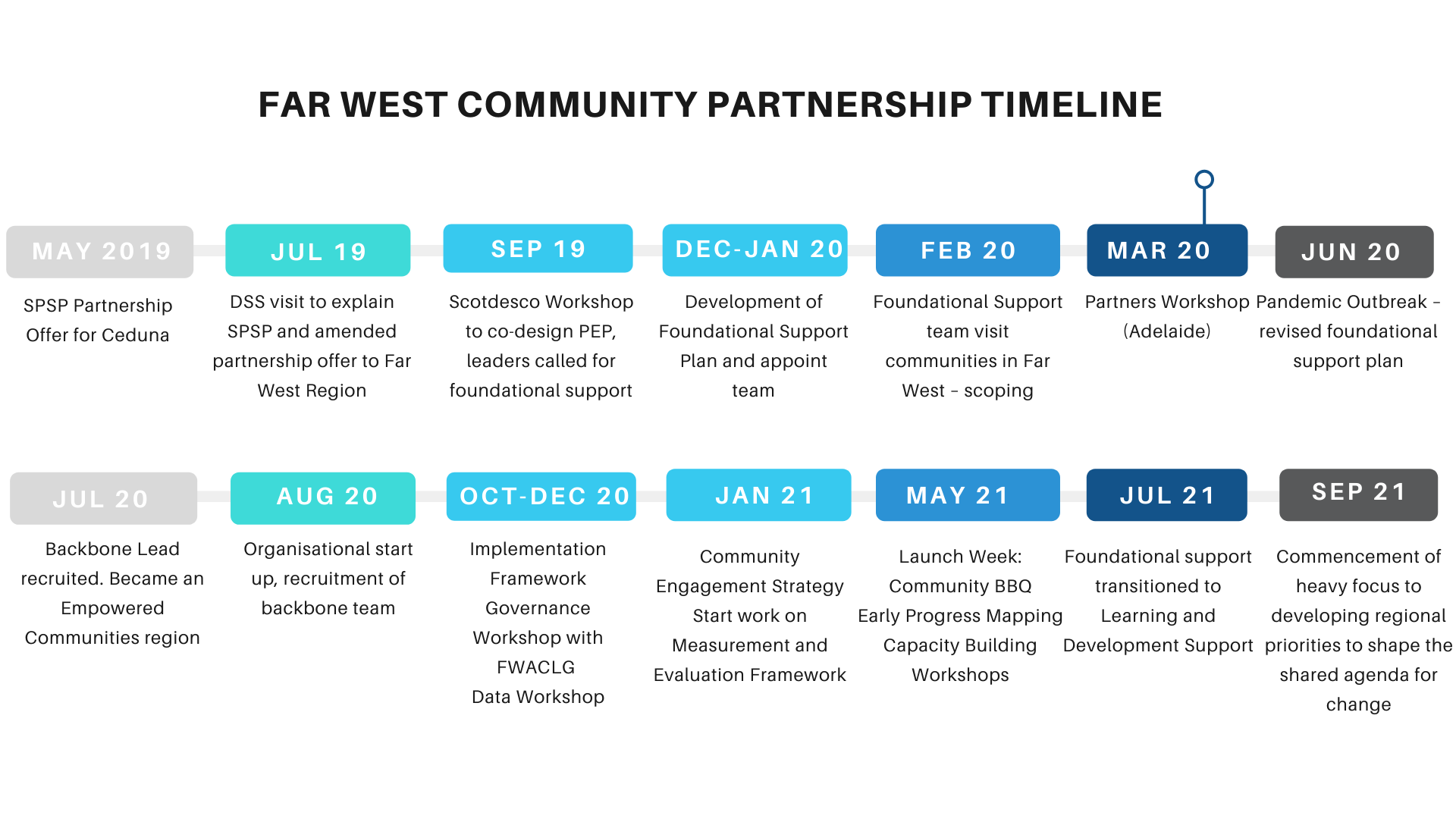

In early 2019 the Commonwealth Minister for Families and Social Services and the South Australian State Minister offered support of the Stronger Places, Stronger People initiative to the Far West Aboriginal Leaders Group. This was followed up in mid-2020 with additional Commonwealth funding for the Empowered Communities Initiative. A shared backbone organisation was established to hold and drive the initiatives, locally named the ‘Far West Community Partnerships’.

Strong and coordinated local leadership contributed to Far West South Australia being selected as a Stronger, Places, Stronger People region. Five CEOs, representing each of the Aboriginal Communities in Far West South Australia[1] had been meeting together for some years and working towards progressing the interests of the community through a regional approach. Additionally, a well-established service collaboration focused on service reform, facilitated by the South Australian Government, had demonstrated considerable success in aligning effort and moving from being in competition to collaboration.

Far West South Australia is a place of natural beauty, rich Aboriginal culture and language, opportunity for business and agriculture, as well as community belonging and resilience. However, a web of indigenous disadvantage continues to persist and a coordinated, community-led approach is needed to build a deep and lasting movement for change.

The Stronger Places, Stronger people offer of a five-year partnership rather than a year-by-year funding model meant that community had enough time to create real change and engage with the community and implement a process that was community led. Importantly, the aim was for First Nations communities to have a genuine seat at the table, be listened to, and a leading voice in decision making.

The partnership with Stronger Places, Stronger People (SPSP) presented the opportunity to create a unified focus on addressing community priorities in the Far West of South Australia.

“My family has been in this area for a very long time as First Nations, tens of thousands of years, and we have continued to play a role in the community through each generation working for our community in the best way that we can, and that's the role that I feel that I've picked up and taken with me in all of the places I've worked. - Jessie Sleep

The first thing to understand about the Far West communities is the sheer tyranny of distance. Each of the five communities are extremely spread out. For instance, Oak Valley is roughly seven hours drive from Ceduna. Each community is also quite diverse in terms of people and needs. Some communities are strong First Nation communities, while places such as Ceduna are more like regional townships.

This creates challenges for meeting and communicating and engagement.

Much of the initial work took place during COVID lockdowns. This made it almost impossible to visit and physically engage. As many of the remote communities had limited internet access or poor service, using Zoom or Skype was fraught.

Yet the Far West Aboriginal Community Leaders Group found a way. The leadership group consists of the five CEOS, each representing the five different communities in the region, had existed as an entity for about seven years. The Far West Community partnerships were very quick to get a communication strategy up and robust messaging, immediately helped to engage with community.

Recruiting the team members

"There was a lot of concern that they may not get someone that'd want to go there and work, and then low and behold, they get a local Aboriginal person there that gets a gig and I just thought, 'That's gold, really'". - Jack Beetson

Another crucial factor has been the recruiting of the backbone team members, themselves community members and deeply motivated to do the work. The recruitment process was very different. Members were recruited for their passion and personalities as well as their core skills, and their ability to contribute to not only the backbone, but to the community,

Jessie Sleep was recruited as the backbone lead. Her recruitment has met with universal enthusiasm and approval. Corey McLennan says she has very swiftly turned things around: “She’s got us leading from the front now, and not only punching above our weight but is way above the timeline as well in relation to where we’re currently sitting.”

Recruiting a backbone team was exhaustive and painstaking and was conducted with a very specific set of criteria. People were selected based not only on their core skills and abilities and personality, but how they would contribute to the backbone and also the community.

“We needed people that could come into a role with a vision, and be able to work in a situation where they weren't handed a book and a sheet of tasks and say, "Here you go, here's your plan, go off and do it," then we're able to work with the staff and work with the community to build what that portfolio needed to be.” - Jessie Sleep

But the biggest operation was creating an actual organisation from the ground up. The Far West Aboriginal Community Leadership Group had to do this on top of their core roles as CEOS. Corey McLennan, CEO of the Koonibba Community Aboriginal Corporation, says it was an extra challenge that took time to deal with:

“That took a lot of work to be able to basically set up a new entity and build a corporation up. We've had to go through all the legal and the legalities of being able to do that, as well as then go through a thorough recruitment process.”

The foundational support helped the leadership group to be reflective quite early, and that was baked into the business approach. This meant an emphasis was placed on internal evaluations and ensuring that there was a cohesive understanding of strategy and process.

The launch of the leadership group was a major triumph, reflective of all the hard work that had gone into laying the foundations. It showed the strong engagement that had already been laid in place as the strong turnout of diverse groups was a testament to.

When Jack Beetson first heard about Stronger People Stronger Places from the co-CEO of Price Waterhouse Indigenous Consulting he was intrigued but also sceptical that government would really allow community-led projects.

“I've had too many years not to be sceptical, but I always live with the eternal hope that people are serious and when I had my next cup of coffee with Gavin a couple of weeks later, I said, "Look, if they're serious, this is a great thing. If they actually come and offer," I said, "But I won't be guaranteeing that they're going to do it." I'm just saying if government's serious about this, it could work.” - Jack Beetson

A seismic shift to the system

A significant challenge was demonstrating that the SPSP process would truly be community-led. Service providers said that this was what was needed, but it required a cultural shift in thinking and a whole change from systems that were, as Jack Beetson says, “submission driven, coming cap in hand to government with a proposal”. And, like Jack, the community were also sceptical, that community would be allowed to drive the process.

"That's what the system's got into it, and I've often said to people that for Aboriginal people, we've gone from fire stick farming to grant farming. That's what the system's done. The other is on the other side of it you've got government that are getting bureaucrats to let go of that level of power. To actually allow their system to be changed." - Jack Beetson

Approaching the community

It was time to change the way communities were approached. It was critical to go in without an agenda, and instead be clearly there to listen and engage. This approach paid dividends in building genuine trust from the community.

“There are a lot of programs and services out there to empower Aboriginal communities but the way that the programs work... with the government, it's so much like you can make a decision, but only if it's the decision that we want you to make.” - Jessie Sleep

It was identified that the first part of the engagement was gaining credibility with the community. Trust had to be built slowly before any action could be taken. Each community had its own nuance and language and rhythms. It was imperative that time was taken to engage and build credibility.

Patrick Sharpe says it’s meant re-educating the community who were used to, what he says was, a “dictatorial” approach, where strict procedures and guidelines had to be adhered to: I'll walk into a community, people say, "Oh, you're here from the health service, you're here to do this, you're here to do that." And it's re-educating them that, no, that's not what I'm here for. I'm here to support you to be more empowered.”

Jessie Sleep points out that the new methodology means there’s an inherent tension between what the community wants and what the community needs: “Sometimes they're not going to be decisions and they're not going to do things that you want them to do, but it's about how you work with the communities through that, instead of deciding when and where they can become empowered.”

Building a community model of success

“Usually what happens is Aboriginal leaders are called on to change things for Aboriginal people in Australia and white people are called on to change things for white people and for Aboriginal people in Australia”. - Sharon Fraser CFI

The Far West model is uniquely different from previous iterations in that the leadership group is composed of Aboriginal community leaders. They drive the agenda and lead all of community. It was a significant shift to have an Aboriginal community leaders group stepping into holding whole of community with the authority of government behind them.

The leadership group has worked hard to make sure that the community feels a sense of ownership over the project. Jessie Sleep points out that as we begin building relationships with more community members across the region, more and more of them are feeling comfortable with us that they will drop into the building unannounced. This building sense of ownership and investment was a key measure of success. This has been due to the patient work that’s gone into slowly building trust with the community.

But with the privilege of community ownership comes responsibility and accountability. This affects service delivery and programs.

“So ultimately, we're doing what's best for everybody and through a process like this, where the people can come back and talk about it. They can have an input in this as well, we're not reliant on people in positions, it's a mass of people that are contributing to that.” - Wayne Miller

Patrick Sharpe says that the FWACLG works hard to authentically engage with the community. This is particularly so with remote communities. Rather than traditional “fly in and fly out” visits of the past, the group go to the community to spend time with them:

“I walked into the community last week and the first thing I did was walk around the corner, rather than staying in the central place community like every agency does. I actually went for a walk into the community itself, into the community proper, and went and visited and had a cup of tea at someone's house. Which they said that was the first time in probably 15, 20 years that they've had someone actually visit them at the house.”

"It feels very much like a partnership. It's very, very much how it's been, so far in the last 12 months or so, it's not a ‘we fund you, you do what we've asked you to do’, it's a, ‘hey, we both want to work towards this outcome, what do you need us to do and what do you need to do?" - Jessie Sleep

It’s worth noting the dramatic shift in the way government interacted with the leadership group. It was no longer a “top-down” approach but a complete transformation in the power balance. It was government stepping back and allowing the Far West Community Partnership to take the reins. This was a very different experience from the past. This not only changed the dynamic, allowing the group to feel more in control of their destiny but also took off traditional pressures such as meeting deadlines and working within a fixed timeline.

Jessie Sleep points out that this space and flexibility given by the government meant that there was no pressure to put together the backbone team in a rush. This meant they could recruit one person at a time and make sure they were getting the best fit for the team and test out the role itself. The whole process was a learning curve and the SPSP model encouraged reflection and an agile method of working, which was supported by the government.

“We've been able to test the waters and launch that role out into the community before we take the next step to understand what complementary roles we need. We've also been able to maintain a line of sight between our governance and community priorities, to what we're doing on the ground, and we've needed time to be able to embed that.” - Jessie Sleep

There was initial scepticism, borne of past experience, that the government would truly be working differently. However, from the initial scoping of the work government offered itself as a partner with the Far West Aboriginal Leaders Group. This was supported by the resourcing of Foundational Support through Collaboration for Impact and Price Water House Coopers Indigenous Consulting.

The trust shown by government toward the community was returned as the leadership group was able to demonstrate its decision-making abilities and show that there was a good structure already in place to roll out programs into the region.

The intent to shift the power to community is there from the government even if the process of shifting systems and changing entrenched behaviour patterns is still an ongoing embryonic process.

Jessie Sleep says that there has already been profound change in the very way government consults and interacts. Their opinion is sought out and valued rather than being an afterthought or a box to be ticked:

"Even just getting a phone call from a government employee asking our opinion on a program before they finish designing it, or if they're going to go out to consultation, asking us about why think before the fact is a huge difference in the way things work."

"One of the early triumphs obviously has been getting all of our governance structures in place, because you can't run any particular entity without the governance side of things." - Corey McLennan

Unique to FWCP is that it has multiple initiatives coming together – SPSP, funded by Department of Social Services (DSS) and Empowered Communities, funded by National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA). These initiatives were being funded by separate government departments and philanthropy. A significant step for FWCP is that the two federal government organisations agreed to jointly fund the one backbone team, working closely with the leadership group to establish the backbone. This created a much stronger, single backbone to drive everything. The five Aboriginal CEOS, each representing a community, sit on the board of directors.

Corey McLennan says it was partly through the strength of their previous relationships with the department they were able to do this and their track record in successfully running leadership programs in the past. He says the formation of a single entity is a much greater value proposition:

“We could actually align and make sure that we get more bang for buck. Bang for buck as in us giving them the key deliverables, us negotiating with the government on that, and then for them to be able to agree for us to be able to carry out this valuable piece of work we're trying to do now.” - Corey McLennan

A collaborative approach is traditionally the way First Nations have worked. This is especially true for Aboriginal people in the Far West, where beyond the state, federal and other organisations there are different indigenous governments from all these different communities, which each have little intricate differences in their governances within those four outlying communities.

Sharon Fraser identifies data as a valuable resource with which to help, inform and understand the issues uppermost in the community. “And if that becomes the way of working around here, then that means you can build sustainable change processes. You can support other people. You can support community to support themselves, to move where they need to move.”

Wayne Miller points out the importance of also sharing resources as well: “And what it's highlighted to us is that there is a number of resources that can be shared to all communities as well, and reduce cost as there's things like data collection, marketing, advertising, these types of things that can be shared and we can continue to grow.”

“You have to keep focusing on it's a community. You're trying to change a community wide effect. And you can't lose sight of that. That's why I keep saying that maybe we should just get it tattooed on our foreheads. Community led systems change, so we remind ourselves of that. - Jack Beetson

“I'd have to be really, really honest in explaining the Collaboration for Impact team has truly been amazing for us. There's no way we could be at the stage we are now, and there's no way we could have been here a year ago, let alone when we started without the support that this particular crew have assisted us with.” - Corey Mclennan

The Foundational Support Team, which was made up of Jack Beetson from PIC, and Sharon Fraser and Brenda Ammann from CFI, worked with the FWACLG and state and commonwealth partners to create and implement a foundational support plan. The purpose was to provide practical support for Far West to build the skills, capacity and knowledge and to establish the conditions for collective impact.

In the early stages this foundational support included developing a deep understanding of the community context that SPSP was moving into . This then moved into codesigning a foundational support plan and then an implementation plan with DSS, SA government and the Fare West Aboriginal Community Leaders.

The Foundational Support work was gaining traction when COVID responses resulted in local community and border closures. Work was then moved on-line, with the CFI-PIC team supporting community leaders in the`’ recruitment of a Backbone lead. The focus then moved supporting the new backbone lead to build a team, building the structures and processes needed to hold the work at this early stage as well as orientating all members to community led Collective Impact.

The work then shifted in the early months of 2020 was to learn from other collective impact initiatives, explore frameworks to help work differently together, establish a backbone and build a leadership and governance environment to enable ongoing commitment throughout the process.

This involved facilitating initial collaborative planning workshops, coaching and recruitment advice and support. It also included hands on help to build processes for community led ways of working, scoping and mapping what had occurred before and initiating conversations with local service providers and leaders through visits to the Far West communities.

Having the support team and foundational support in place from CFI and PIC enabled the backbone team to set up and understand the work and the processes. It’s a valuable safety net which drives the rest of the project.

For the FWACLG it was a steep learning curve of new processes, a new way of doing business and a new mindset. Having the CFI team giving them vital support assisted them in not just learning, but with the legalities of setting up organisations, the recruitment drive and all the organisational structures and policies.

They not only opened our eyes from way back in the early days to how we could possibly garner this and get it up and running and weigh up the initial stages, you know? Us as a leader’s group, way before literally got announced here, we were not only meeting with the government of the day and the department of the day that funds the program, funds the social services. - Corey McLennan

The support of PIC and CFI’s in bringing in the concept of collaborative impact into the region has been a huge game changer that has revolutionized thinking. Says Pia Richter:” it’s helped to extend the thinking around these things and for people that don't understand about collaborative impact, it's introduced that whole concept to the community. In my time, that hasn't been done before.”

The early support provided to the community was invaluable in terms of not just upskilling and education around some of the concepts and the models that the community was working with, but gave them the opportunity to bounce and play around with ideas.

The foundational support team orientated Jessie and new backbone staff to systems approaches, through online tailored workshops focused on specific topics, such as collaborative governance and inclusive community engagement. Regular weekly coaching, sharing resources and co planning enabled a smooth transition from the work being held by foundational support to the team on the ground. Some key early pieces of work that were developed together include the communications strategy and the community engagement strategy.

Foundational support also brought together key resources to align the work of measurement, evaluation and learning to set up a data working group to establish a framework and processes, theory of change that could be iteratively developed according to the community change agenda and digital data warehouse with the opportunity for Aboriginal data sovereignty.

The community has enthusiastically taken to collective impact and the support provided by CFI and PIC has been vital to this.

You've challenged our mindsets and our thoughts in relation to this is an exciting new adventure. This is something different. This can be a game changer, you know? We're all leading in our communities and we're all operating under a certain way that we normally operate. - Corey McLennan

"This is the beginning and hopefully two to three, to ten years down the track, we'll see many more benefits for our people and our kiddies. Our kids are our future and we need to invest in it." - Corey McLennan

The success of the Far West has been displayed in a number of ways: creating a solid foundation that can be built on to deliver successful programs to the community; empowering and engaging the community and giving the FWACLG the tools and mindset through collective impact to deliver change.

Jessie Sleep says that the possibilities are now very real and there is a real readiness to do something collaboratively by all five Far West communities.

“And I think that there are some lovely foundations that have been put in place around that. I really look forward to how the Far West community partnership now steps into building and driving its community aspiration or its shared agenda. I think that it is ready to rock there. It's ready to go” - Jessie Sleep

Success is five Aboriginal community leaders making up the entire FWACLG. This is a profound change that spearheads the direction of being led by community. It also means the leadership group is made of people who understand the day-to-day issue and difficulties facing the communities. This leads to authentic voices working for the community.

Says Pia Richter: “I just think having an organization focused on particularly the First Nations voice is very important because that's a gap in the region and that has been, and that will benefit every organization and the community. “

It’s also sparked enthusiasm and excitement amongst the backbone team and given them personal insights into their own journey. Says Jack Beetson:

"I'll tell you what it has done. It's taught me a lot of patience in working with people, because I'm involved now in five in one way or another, and just having the patience that every time you go in with this particular initiative, you're actually making a road as you go in each community. You have to go in and before you even get there, acknowledge that there's going to be different characters, there's going to be different characteristics, there's going to be different motivations for people to be involved in it. And motivations not to be involved."

There is also a recognition that not everything can be resolved straight away but that there are ongoing discussions and communications that need to take place. For instance Jack Beetson says: ”How do we get people to stop thinking project and think this higher level systems change? That will ultimately deliver down there in a project way, or better projects, or better system to deal with projects, but how do we get people to make that shift?”

This ongoing discussion and recognition of where things need to go, is also success. There’s a realisation that there’s an ingrained way in which services have been delivered over forty years and, consequently, this has led to a particular mindset. Jessie Sleep says that success is being able to reset the mindset and help the community welcome a new way of working together.

She points out that, despite the excitement and enthusiasm of the team, it’s important to work at the right pace.

"We've got so many great ideas, and our community is on our doorstep, and we would love to just go out there and do everything, but we know for the long-term that would be quite dangerous to try to push through too quickly early. So, it's difficult and it's a challenge to put the brakes on. We've got so many great ideas, and our communities is on our footstep, and we would love to just go out there and do everything, but we know for the long-term that would be quite dangerous to try to push through too quickly early.”

This is my cusotm heading

Other case studies

Change Cycle Locator Tool

Take the quick survey to work out where you are on your change journey and access information specific to your needs