Building Governance for Purpose: A reflection piece

By Sharon Fraser, CFI Network member

When we talk about governing for purpose, we are committed to governing in a collaborative way or in ways that reflect cultural differences. When we then start our work together, we find that we produce traditional governance structures and processes. After all, we know how to do this. In this piece, I share my reflections on how traditional, collaborative and cultural governance can be held together to deliver effective governance for purpose.

Just to step back, let’s unpack some concepts:

• ‘traditional governance’ refers to the framework of rules, relationships, systems and processes by which an enterprise is directed, controlled and held to account and whereby authority within an organisation is exercised and maintained.1

• ‘collaborative governance’ is the way collaborations organise themselves to achieve their goal. It is inclusive of processes, structures, and dynamics of decision making and coordination, across organisational and sectoral boundaries including community.2,3

• ‘cultural governance’4- is the ways that our First Nations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander) people, organise themselves and make decisions in ways that have been around since before colonisation.

Start with Commitment?

Traditional Governance systems, like any system, are self-sustaining and reinforced across many aspects of those systems. Consequently, the commitment to convene and make decisions in collaborative ways or to embed cultural practices needs to be strong and held broadly across the work. I frequently see a documented commitment to collaborative and cultural governance for initiatives across Australia. However, both fade in practice.

So, our commitment needs to be not only documented but actioned.

How we Action Governance for Purpose

Of note, governance for purpose is not a choice between these three ways of governing but a bringing together of the three in ways that fit your context, in your community for your purpose.

Traditional Governance

For initiatives to be funded, especially the backbone role, governments and other funders such as philanthropy need to be able to fund an organisation that can hold its fiduciary responsibilities. The contractual arrangement resulting needs to be held in ways that are transparent and accountable. Of note, whether this is through one of the partnering organisations or whether there is a separate incorporated body, when I have seen this held well, the funded entity holds the funding and accountability and does not use this as a way to direct or hold power over the work of the initiative.

Traditional governance is best seen as an enabler for the work, but it is not the work itself. If the conversation around the initiative’s leadership table is about how money is being spent - opportunities for significant change can be lost.

The challenge is for the funded entity to align its work to the purpose-driven collaborative efforts and not to the accountability of funders or their own organisational needs.

Collaborative Governance

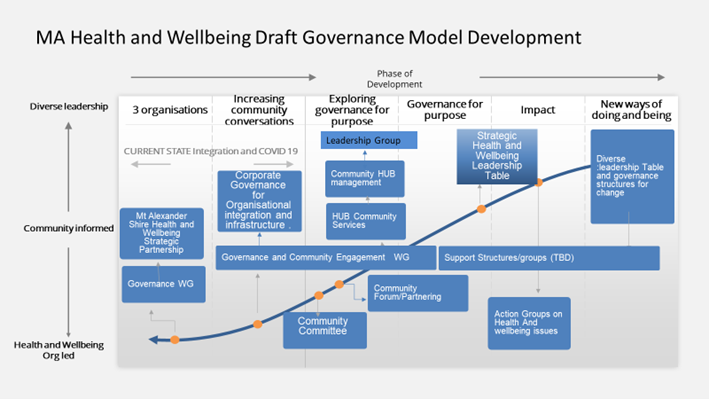

Building collaborative governance is best done over time with structures and processes reflecting what is needed at any point in time. Planning and setting direction for Collaborative Governance is strongest when this is seen as a learning journey rather than a recipe. One such example can be seen in the following where partner organisations are moving overtime to bring community into decision making and to shift the initiative to becoming community-led:

Further examples of the development of collaborative governance at different phases of initiative maturity can be found in Collaborative Governance: An introductory practice guide.

Convening for collaborative governance still needs to be structured but it can be less formally held with, for example, by using run sheets rather than agendas and meeting notes rather than minutes. In addition, effort needs to be taken to ensure that shared inclusive language is used across the work. Decisions are made within defined structures and processes, with these being made as close to the community as is possible.

Cultural Governance

In my experience, cultural governance is frequently hidden or not understood by those outside of the culture and appears to vary across ‘nations’, language groups and at times ‘family groups’. In addition, everyone educated in Australia in the last two-hundred years has been colonised to some extent, so some of this has been lost or re-imagined.

Initiatives working to embed cultural governance are often looking to local First Nations people for guidance and asking questions about the cultural systems locally. This does not always deliver as it may not be culturally appropriate for these to be shared. To overcome this some initiatives embed general First Nations rhythms in the ways they convene, for example, convening by a sitting circle and ensuring all voices are heard or not making decisions until all culturally required conversations can happen. This is strengthened when the initiative is First Nations-led and/or local First Nations people are employed in key backbone roles. This plays out very differently across urban, regional rural and remote Australia.

Weaving it together

Delivery of significant change requires the weaving together of these three governance rhythms. This is achieved by a clear articulation of purpose and principles for the work that will inform not only structures and processes but the use of power and the mindsets and attitudes required to deliver.

Where I have seen this done well in initiatives, I see:

• traditional governance being held strongly and in the background, ensuring resourcing integrity for the initiative;

• collaborative governance being developed over time with structures and processes reflecting what is needed now, based on learning from our data and the community; and

• cultural practices and First Nations people being respected in both convening and decision-making processes, with decision making moving at the speed of the community cultural practices.

I would be interested to know what you have seen working in governance across social change initiatives in Australia.

Sharon Fraser is Founding Director of Clarion Call and a CFI Network Member.

For further reading download > Collaborative Governance: An Introductory Practice Guide

1 Standards Australia, Good Governance Principles, AS 8000-2003, 23 June 2003, 10–12 (Governance Standards);

2 Emerson K, Nabatchi T, Balogh S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. JPART [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2020 June 21]; 22: 1-29. doi:10.1093/jopart/mur011

3 If you want to explore these concepts in detail including the difference between the two I refer you to Collaborative Governance: An Introductory Practice Guide here on Platform C.

4 To be clear I am a white Australian and reflect this concept from what I have seen and understand, consequently, it is by no means holistic.